Camp Hughes

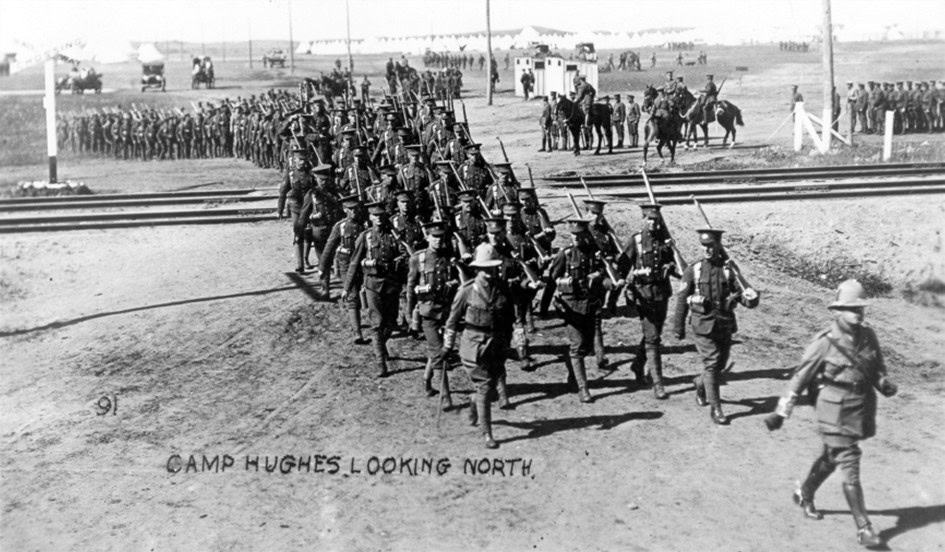

During the First World War, the Canadian Militia established a network of military training sites across Canada to train six hundred thousand recruits for the Canadian Expeditionary Force going overseas to fight on the Western Front. One of the seventeen training sites was Camp Hughes near Carberry, Manitoba, 132 kilometres west of Winnipeg, south of the Trans-Canada Highway. The Canadian Militia trained upwards of thirty-eight thousand recruits at Camp Hughes in 1915 and 1916. In 1916, it was the second-largest training camp in Canada and the second-largest community in Manitoba. Today, Camp Hughes is a Provincial and National historic site containing one of the only First World War trench systems.

In 1909, the Canadian Militia proposed land between Sewell Station and Carberry, with direct access to the Canadian Pacific Railway, as a suitable location for the main summer training camp for District 10. The district included Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and the District of Keewatin, Kenora, Rainy River, and Thunder Bay. The Canadian Militia obtained the necessary approvals for an initial summer training camp in June 1910, with 154 officers and 1,315 men attending.

In 1915, the CPR changed the name of Sewell Station to Hughes Station. The Militia also renamed the camp, in honour of the Minister of the Militia, Lt. General Sir Sam Hughes, K.C.B., to Camp Hughes. The main features of Camp Hughes were 10 kilometres of trench system, a rifle range, grenade grounds, artillery ranges and observation posts, and a cemetery. In 1915, 414 officers and 10,580 men trained at Camp Hughes. In 1916, the numbers increased to 880 officers and 25,067 men, with an additional 1,600 staff responsible for training recruits. In the summer of 1916, Camp Hughes was the second largest camp in Canada, training approximately 26 thousand, behind Camp Borden, which had 30 thousand.

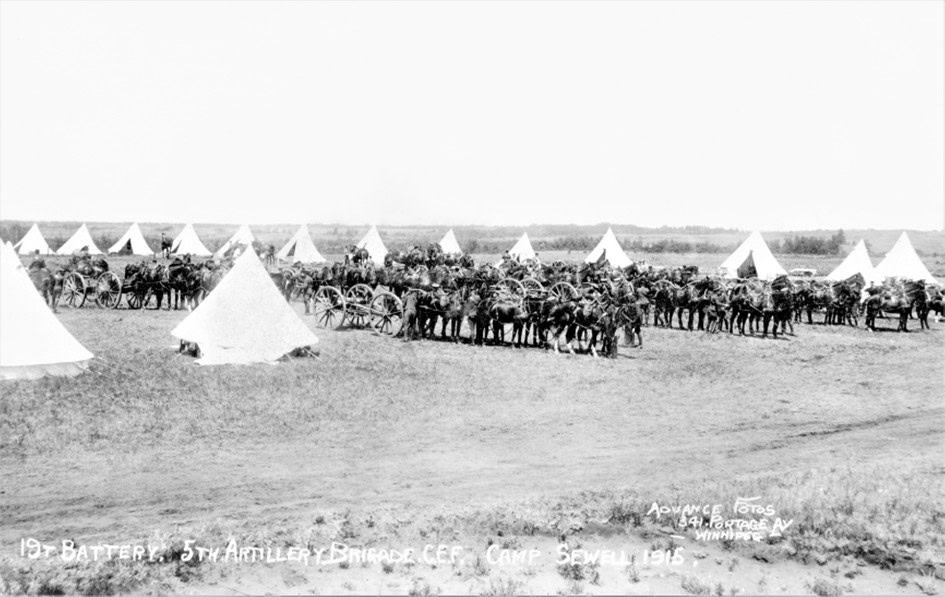

During the First World War, the Militia sent mainly infantry and artillery troops to Camp Hughes. For example, in June 1915, the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Batteries C.F.A. (all part of the 5th Brigade) moved to Camp Hughes for training. In 1915, the 37th and 38th Batteries also trained at Camp Hughes. At Camp Hughes, they had two new Mark IV 18-pounders and a full complement of obsolete 12-pounders (Canadians used this gun during the Boer War). Each battery relied on horse-drawn artillery, and the 12-pounder was good for mounted manoeuvers. A pre-war field artillery battery required four 18-pounder guns. When war broke out, the Canadian Expeditionary Force upgraded to six 18-pounder guns per battery, matching the British, causing many artillery batteries to be combined or redistributed.

Camp Hughes is known for its extensive trench system that still exists today. The Militia completed the replica trench system in 1916, and veterans returned from France to train the recruits. The trench was realistic and full-scale, allowing for the training of 1,000 soldiers. The recruits learned to fight in conditions similar to the Western Front, training for twelve weeks in the trenches and rifle ranges. Each battalion trained in the trench network, establishing daily routines, sentries, listening posts, and going over the top into the no man’s land. The soldiers would enter the trench system through the communication trenches that led to support trenches, then to the frontline trenches.

The frontline (fire) trench is approximately 1 km long and could hold two companies of men. The trench system also included underground dugouts designed to protect soldiers from artillery bombardment. The Militia also built shallow enemy trenches on opposing high ground, similar to German defences on the Western Front. They also had a two thousand-yard-long rifle range with 500 targets and a grenade school where they practiced throwing live grenades into designated pits.

In 1915 and 1916, the Militia made many infrastructure upgrades, adding buildings along the boardwalk and other areas, including an Army Service Station, bake house, bake ovens, guard house, hay storage, and veterinary hospital. They added a camp commandant hut, a headquarters building, a hospital, a medical supplies building, a photo studio, a post office, a prison, and a target house. The hospital at Camp Hughes accommodated over 300 patients. In 1916, the hospital treated 3,815 patients, with 11 reported deaths (six buried in the Camp Hughes Cemetery). The camp also had a bank, a barbershop, a camp newspaper, grocery stores, a milk depot, six movie theatres, and even a heated, in-ground swimming pool. Business owners placed restaurants and laundries outside the camp.

After 1916, the Canadian Expeditionary Force stopped training at Camp Hughes due to a lack of recruits and the introduction of conscription. With less need for military training sites, Camp Hughes closed in 1917, including all the businesses on the boardwalk. After the First World War, the Militia reopened the camp for summer training and continued operations until 1933. Back in the 1920s, Camp Hughes contained 138 square miles of training ground, including swamps and bogs, which was not conducive for military training. The main reason for moving it 15 miles south to Camp Shilo was the poor and unsuitable land at Camp Hughes. In 1934, the Militia dismantled Camp Hughes, with some buildings relocated to the newly established Camp Shilo.

Many battalions and batteries that trained recruits at Camp Hughes distinguished themselves in battle during the First World War. Many fought in France and Belgium, including at the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, Passchendaele, Amiens, and Cambrai. For example, the Fifth Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery trained at Camp Hughes, then bombarded Vimy Ridge for three weeks before the Canadians advanced and took the ridge on 12 April 1917. Canada mobilized 620,000 during the war, with a 39% casualty rate, 67,000 killed and 173,000 wounded. Many soldiers that trained at Camp Hughes never made it home, with the camp representing Canadian service and sacrifice.

For a hundred years, residents used Camp Hughes as pasture land, and the trench system has faded into the landscape due to natural erosion. Today, Camp Hughes consists of 10 kilometres of trenches in various states of decay. The original buildings are no longer on the site, and the dugouts are gone, but indubitably artifacts remain below the ground surface for future discovery. Visitors can pay their respects at the cemetery containing six soldiers that died while training. They can walk the 10 kilometres of First World War trenches and experience Canadian history and heritage.

By Andrew Oakden