The Boxer Time Fuse

Fuses may not be the first objects visitors expect to encounter in a museum, yet they are essential to understanding how artillery functioned. Without a reliable fuse, even the most advanced gun and shell could not perform as intended, making these small components central to the history of artillery warfare.

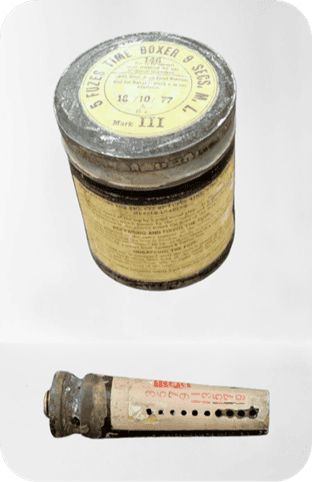

In a sleek display case, four Boxer time fuses are shown alongside their original manufacturer’s tin, dated 13 October 1877. One fuse is displayed separately, while the remaining three remain housed in their well-preserved container, produced by the Royal Laboratory at Woolwich, England. All four are made of wood, rendered inert, and originate from the same production lot, as indicated by their sequential numbering. The tin lid is marked “5 Fuses Time Boxer 9 Secs ML,” identifying their use with muzzle-loading artillery.

At the time of Canadian Confederation in 1867, Canadian artillery relied on smoothbore guns fitted with two principal types of fuses: time and percussion. The most common time-delay fuse in service was the Boxer fuse, developed in 1853 by Colonel Edward M. Boxer of the British Royal Artillery. Its introduction marked an important advance, allowing gunners to control when a shell would burst rather than leaving its effect to chance.

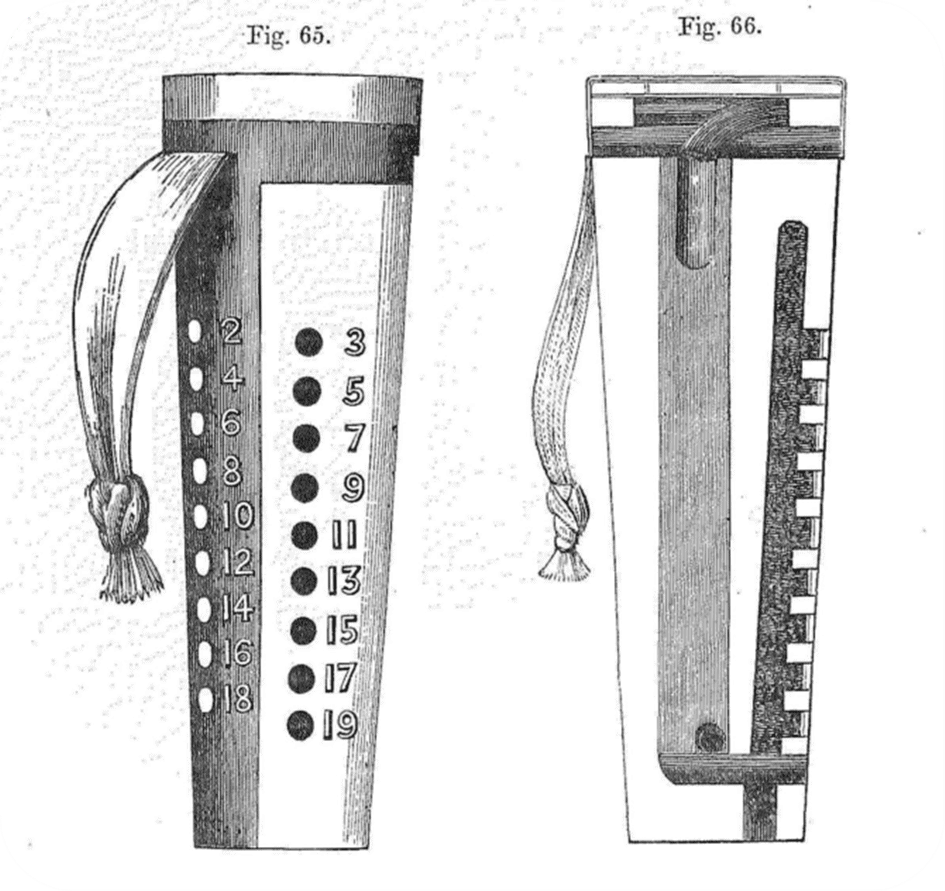

Earlier time fuses used less dependable ignition methods, often producing uneven burn rates and unpredictable results. The Boxer fuse addressed these problems through intersecting powder channels that burned more consistently and could be adjusted with greater precision. This reliability made it widely adopted throughout the British Empire and trusted in both training and combat.

Boxer fuses are conical in shape and contain a central powder train that burns at a standardized rate of approximately five seconds per inch. By selecting the appropriate boring hole, the gunner could set the desired delay to match the shell’s time of flight. The examples displayed here are set for a nine-second burn, after which they would ignite the shell’s bursting charge.

These particular fuses are Mark III Boxer fuses, a pattern issued for general use with field, garrison, and coastal artillery, and authorized as a substitute when other marks were unavailable.

To preserve their effectiveness, the tin bears the instruction “not to be opened until required for use or special inspection.” Printed instructions inside guided gunners unfamiliar with the fuse. Preparation required seating the fuse firmly into the shell’s fuze hole, sometimes with a wooden mallet, and removing protective coverings to expose the primer before loading.

When the gun was fired, propellant gases passed through the windage between the shell and the bore, igniting the primer and starting the fuse’s powder train. As the shell travelled downrange, the fuse burned for the selected interval before igniting the bursting charge, causing the shell to function at the intended moment.

The Boxer fuse represented a significant improvement in controlled artillery fire. By allowing gunners to determine when and where a shell would burst, it played a key role in the effectiveness of both smoothbore and early rifled artillery during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

By Andrew Oakden