The No. 106 Fuse during the Battle of Vimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge is Canada’s most celebrated military victory during WWI. Yet few remember the extensive artillery bombardment before the battle or the highly effective use of the instantaneous No. 106 fuse.

Over 35,000 British and Canadian troops operated over 1,000 guns and fired 1,000,000 rounds, bombarding the ridge for three solid weeks, from March 20 to April 9, 1917. They focused on barbed wire, dugouts, machine-gun emplacements, trench junctions, tunnel entrances and strong points. Canadians destroyed 83% of enemy guns with counter-battery fire and cleared wide paths of barbed wire defences, allowing the Canadian Corps to advance and take the ridge on April 12, 1917.

The Canadians didn’t attempt to destroy all the enemy trenches. Instead, they went after wire entanglements and barbed wire defences to clear paths for the infantry. To remove the barbed wire, they used the new instantaneous No. 106 fuse with high explosive shells that detonated on impact with barbed wire. They used it mainly with 18-pounders, 4.5-inch howitzers, and 6-inch guns.

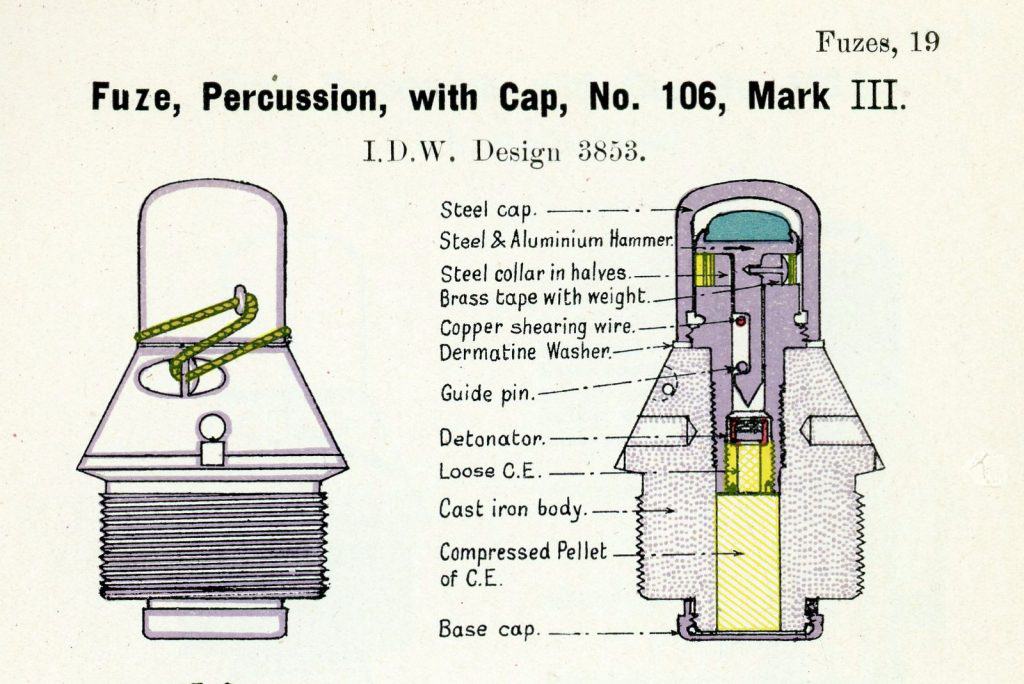

No. 106 fuse on display at the museum.

The British and the Allies began the war with field guns firing shrapnel shells with time and percussion fuses that burst over the heads of enemy soldiers. Traditional percussion fuses were slow to explode and commonly penetrated the ground before exploding. Shells would land in mud, bury, and explode, and the earth would absorb the energy. Traditional fuses did not work effectively with trench warfare.

The British experimented with graze fuses in late 1915, but they were not instantaneous and lacked sensitivity, causing delays in firing explosive charges. They did not consistently explode on soft targets, including trench walls and barbed wire. The solution to this problem came with the invention of the instantaneous percussion fuse, No. 106. The fuse used French technology to reliably detonate a high-explosive charge when it contacted any object, including barbed wire.

To operate the fuse, the Gunner removed the safety cap, loaded the projectile with the fuse attached, and fired the gun. The projectile with the fuse accelerated violently through the barrel, pulling back the hammer. When the shell left the barrel, the speed dropped and caused the hammer to move forward in the readied position. The projectile flew and then hit a target. The hammer, with an axial rod, retracted, hitting the detonator cap and causing an instant explosion.

Diagram of No. 106 fuse from Handbook of Ammunition, 1918.

Trench warfare required high explosive shells with instantaneous fuses that destroyed enemy formations upon contact. The British started using the No. 106 during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, with widespread use in 1917. The new fuse worked very well and detonated with the slightest impact. The ultra-sensitive, direct-action fuse even exploded on soft ground. Only physical contact with the protruding hammer or the nose of the fuse caused detonation. Protection included a soft aluminum cap that absorbed glancing blows, reducing misfires.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge set a new standard for artillery support to deal with well-defended enemy positions and counter-battery attacks. Canadians used the No. 106 fuse extensively during the battle until the war ended. It was a highly effective, instantaneous, direct-action percussion fuse for barbed wire removal and counter-battery fire. In a later version, No. 106, Mark VII added a secondary safety mechanism that reduced misfires. Versions of the fuse remained in service into World War II.

By Andrew Oakden