The Riel and Drury 1885 Notes

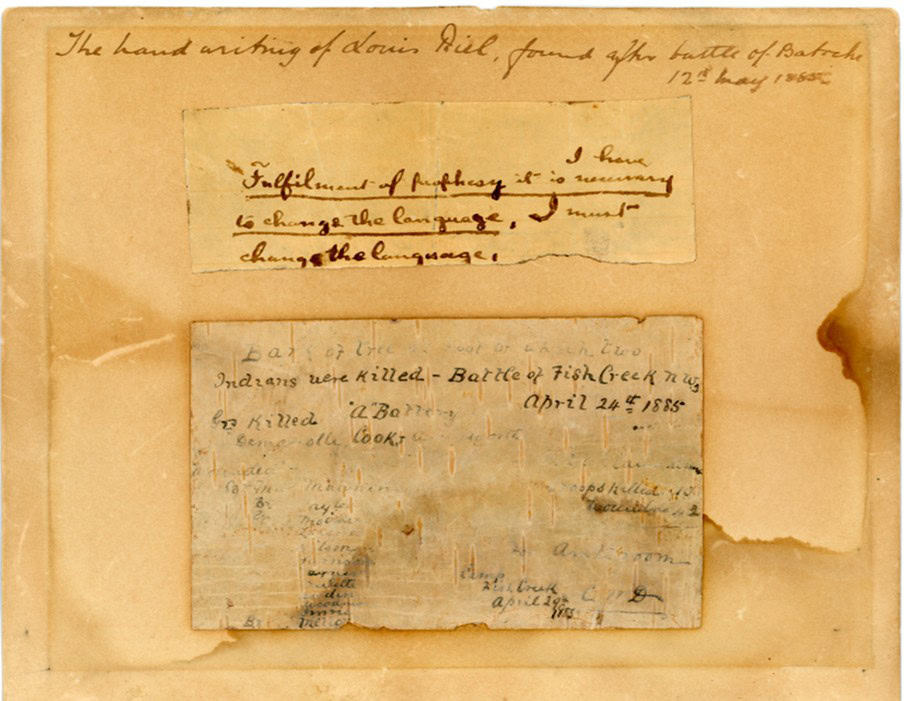

The RCA Museum has two handwritten notes from the North-West Rebellion or North-West Resistance. Louis Riel purportedly wrote the first note found after the Battle of Batoche, dated 12 May 1885. Captain Charles W. Drury wrote the second note on birch bark after the Battle of Fish Creek, dated 29 April 1885. Both are exceptional discoveries that help explain a controversial moment in Canadian military history.

In March 1885, a group of Métis led by Louis Riel started an uprising against the Canadian government in the Districts of Saskatchewan and Alberta called the North-West Rebellion or North-West Resistance. Some Métis thought the federal government was not protecting their rights, land, and economic prosperity. They lost revenue from the waning fur trade and the loss of the seasonal bison hunts. The 1885 uprising also included an associated revolt by First Nations, who faced starvation due to the disappearance of bison herds and the loss of land from treaty agreements.

The Riel and Drury Notes from 1885 at the RCA Museum.

In 1884, Louis Riel returned from exile in the United States to lead the Métis resistance. Most of the Métis and First Nations in the North-West stayed out of the fighting. On 26 March 1885, a group of Métis under Gabriel Dumont clashed with the North-West Mounted Police at Duck Lake in the District of Saskatchewan. On 2 April 1885, at Frog Lake, a party of Cree killed nine settlers. In response, General Middleton gathered his forces at Fort Qu’Appelle in March/April 1885, including A and B Batteries and militia Gunners serving as infantry. The Winnipeg Field Battery activated for service (now 13th Field Battery in Portage la Prairie). During the hostilities, the Métis had notable early victories at Duck Lake, Fish Creek, and Cut Knife.

The handwritten notes from the 1885 uprising are in relatively good condition considering someone glued them to cardboard at least fifty years ago. Today, we would never glue artifacts directly to a display mount because doing so would likely damage them over time. The fountain pen ink has faded in parts, probably due to prolonged exposure to light and water damage, and it may not be easy to display these artifacts in the future due to conservation concerns.

On the back of the cardboard, it says: “Presented to the RCA Museum by 1 RCHA.” We have no presentation date, but it likely occurred in the 1960s. We have an article from Reader’s Digest, Explore Canada 1974 Edition citing the two 1885 notes on display at the RCA Museum. Clive Prothero-Brooks, the museum’s long-term collection manager, confirmed they were on display until 2002.

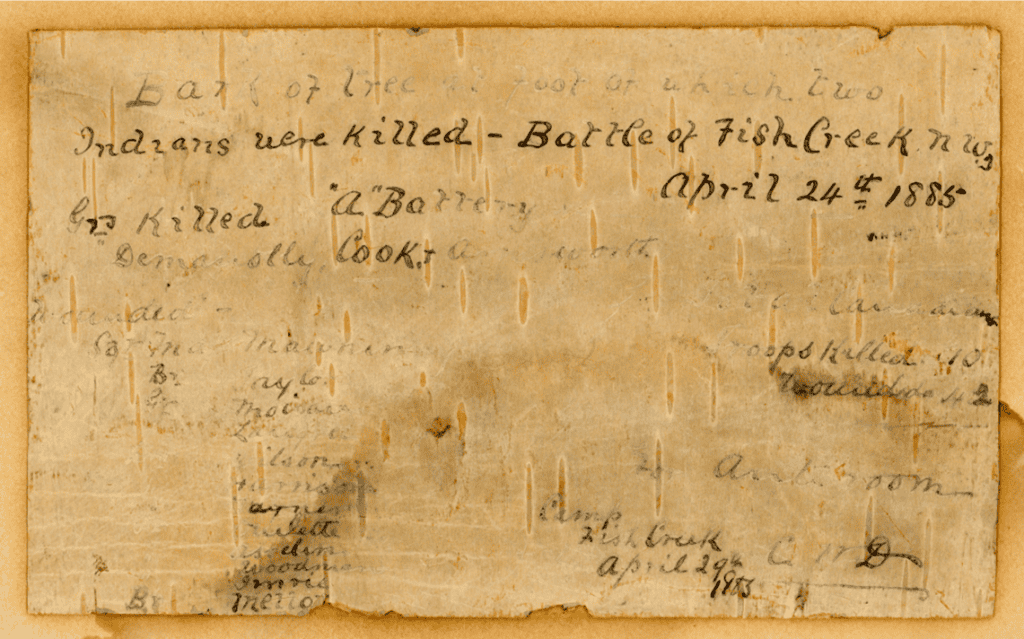

The Drury note reads in part: “Bark of the tree at foot of which two Indians were killed – Battle of Fish Creek. N.W. – April 24, 1885.” The words used to reference First Nations have changed during Canadian history. In this case, the message contains a now derogatory term; however, one hundred years ago, this was not considered as such. The author was Captain Charles W. Drury, the acting commander of A Battery, who later became a Major-General and RCA Great Gunner known as “the Father of Modern Artillery in Canada.”

MGen Charles W. Drury

General Middleton split his force in two before engaging the Métis and First Nations at Fish Creek in the District of Saskatchewan on 24 April 1885. Each force advanced down either side of the South Saskatchewan River.

The battle started with 150 Métis and First Nations ambushing the scouting party of federal troops at Fish Creek, which was 20 kilometres south of Batoche. The Métis and First Nations then retreated to ravine dugouts along the river. Once attacked, General Middleton ordered shelling of the ravine dugouts, which failed to dislodge the Métis and First Nations.

Handwritten note on birth bark by MGen Drury from Battle of Fish Creek.

The Métis and First Nations held their ground, and the soldiers pulled back after heavy fighting, halting Middleton’s advance. The old-style lead bullets from the rifles caused terrible injuries to the combatants on both sides. After the battle, dead horses also littered the battlefield. Ten soldiers died at Fish Creek, and an equal or larger number of Métis and First Nations died during the battle. The Drury note represents an eyewitness statement of the military casualties during the Battle of Fish Creek. The reported dead included three from A Battery: Gunner Ainsworth, Gunner Cook, and Gunner Demanoilly – these were the first Permanent Force casualties in Canadian military history. Drury then lists the names of wounded gunners and the number of overall troop losses and signs it: Camp Fish Creek – April 29, 1885, CWD.

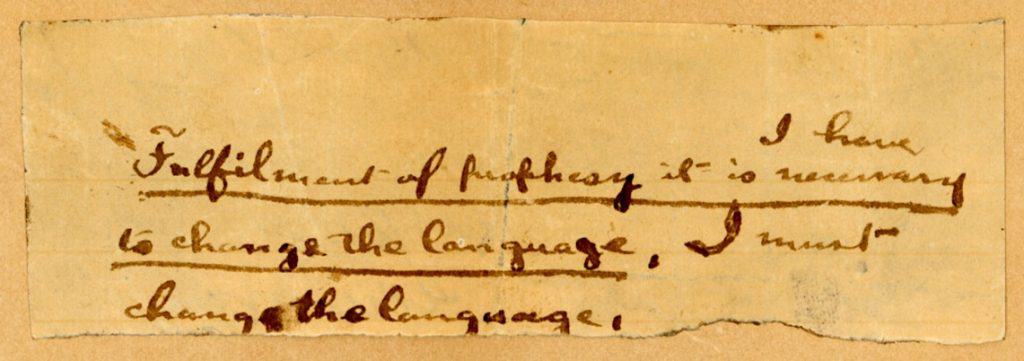

On the Riel note, the script says, “I have fulfilment of prophecy – it is necessary to change the language. I must change the language.” Above this text, museum staff confirmed that Louis Riel wrote the note found after the Battle of Batoche on 12 May 1885. Riel added a religious element to the uprising, which is evident in the note’s subject matter.

Handwritten note by Louis Riel found after the Battle of Batoche.

During the Battle of Batoche, federal forces with the guns of A Battery and the Winnipeg Field Battery militarily defeated the Métis on 12 May 1885. Each morning, from 9 to 12 May, troops advanced on Métis lines, then retreated at night. On 12 May, on the fourth day of advances, Middleton’s forces overran Riel’s forces. The Battle of Batoche ended the Métis insurgency and led to Riel’s arrest for treason. The Alberta Field Force under General Strange, with the Steele Scouts, continued the fight at Frog Lake and then Frenchman’s Butte with First Nations warriors. The last shots of the rebellion came on 3 June, at Loon Lake, Alberta.

Louis Riel

As museum director, I can attest that our collection has no other artifacts like these. However, the aftermath of the uprising, including the execution of Louis Riel and the marginalization of Métis and First Nations, remains a polarizing and controversial moment in Canadian history. The rebellion left dozens of Métis fighters and First Nations warriors dead, and federal forces lost 38 soldiers with 141 wounded and 11 civilians perished.

From the perspective of a military museum, we want visitors to remember and re-evaluate the 1885 uprising. Building a nation relies on individuals or history-making agents. These historical figures, such as Louis Riel and Captain Drury, have important stories to tell with far-reaching historical consequences. Back in 1885, two men on opposing sides wrote these notes, which provided eyewitness perspectives to the story of the uprising. While we may question the lasting importance or legacy of the 1885 uprising on Canadian soil, we cannot forget that these events happened.

By Andrew Oakden