A Rusty Shrapnel Round

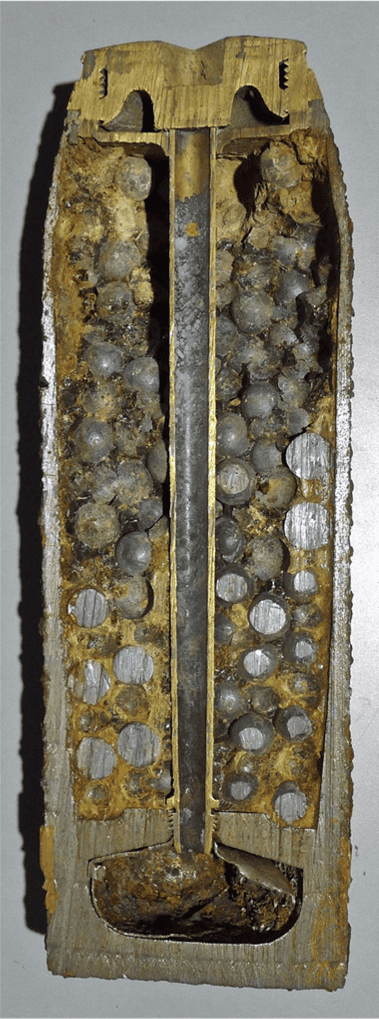

In 2017, as museum staff prepared for the Austin Thresherman’s Reunion outreach event by collecting artifacts for display, I noticed a very rusty half-casing on the shelf at our secondary archival facility. When I leaned in to examine the shell, I saw dozens of musket ball-sized lead bullets caked in tar, shown below. I remember wondering what round used such an unusual and complicated payload. Fast forward to 2022, I can identify the round as an 18 Pounder WW1 shrapnel shell – a long-range anti-personnel munition with a long and distinguished history.

In the early 19th century, the British Artillery deployed smoothbore cannons, such as the 9 Pounder SB, which fired solid shots, shells (a hollow cast-iron round with gunpowder in the centre), or a canister round – a short-range anti-personnel munition. As the distances between the Artillery and the opposing forces increased, Gunners needed new and more technologically advanced munitions that spread destruction at ever-increasing distances. The British lacked an effective anti-personnel shell for longer ranges – the shrapnel round or spherical case shot solved this problem. The shrapnel shell combined the lethal canister round effect with a long-range fuzed projectile.

Major-General Henry Shrapnel (1761–1842) from the Royal Artillery in Britain started developing shrapnel ammunition in 1784, and the British adopted the shell in 1803. Lieutenant Shrapnel served in Newfoundland early in his career, which gave him a Canadian connection. When fired, the munition flew towards the target, with a time fuze igniting a propellant charge, blowing off the top of the shell casing and ejecting the lead bullets towards the target. The metal casing was not lethal; its function was to transport the lead bullets.

The British used shrapnel ammunition extensively during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) and Crimean War (1853–1856). The munition underwent many changes and improvements over the nineteenth century. However, the shrapnel round always used lead balls or shots that relied on the shell’s velocity for lethality.

During the First World War, all sides used shrapnel rounds for long-range anti-personnel ammunition. Gunners fired tens of millions of shrapnel rounds, resulting in high casualty rates during the war. It was highly effective against troops in open formation but less effective in trench warfare – the ammunition did not penetrate the earth or trenches. Canadian manufacturers produced about one-third of the shrapnel rounds for the war effort from 1914 to 1918.

In the latter stages of the First World War, the shrapnel ammunition was phased out and made obsolete. The shrapnel round was expensive to make and not as effective as the modern High Explosive (HE) round. The HE shell had similar but more effective anti-personnel attributes. HE rounds used high explosives to explode the metal casing into thousands of tiny shards of shrapnel – it was a different means to use shrapnel, but certainly part of the evolution of long-distance anti-personnel ammunition.

The shrapnel munition was an effective anti-personnel shell for longer ranges, notably from 1803 to the end of the First World War. Canada still had rounds for some howitzers into the 1930s, but HE rounds were more effective by this period. The shrapnel munition is still used by some armies around the world today. This round will be displayed to help explain the history of ammunition and the Canadian Artillery in the First World War.

By Andrew Oakden